The Monty Hall problem is a classic entry-level problem in probability, named after the original host of the TV programme Let's Make A Deal, which aired in the United States from the 1960s. While the problem originated in Selvin et al.'s 1975 letter to The American Statistician, it became famous from a reader letter submitted to Marilyn von Savant's column in Parade magazine. From Wikipedia:

Suppose you're on a game show, and you're given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what's behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, "Do you want to pick door No. 2?" Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?

It's worth reading the Wikipedia article in full as the historical background is equal parts astounding and infuriating. von Savant got the problem exactly right, but many others didn't, with a selection of the latter chose to write highly misogynistic and degrading responses to von Savant for years afterwards, even after she explained multiple times, in multiple ways, the correct reasoning. You can check out some of the responses at this web archive page. A couple of personal favourites are:

Maybe women look at math problems differently to men.

— Don Edwards, Sunriver, Oregon

May I suggest that you obtain and refer to a standard textbook on probability before you try to answer a question of this type again?

—Charles Reid, Ph.D., University of Florida

I am sure you will receive many letters on this topic from high school and college students. Perhaps you should keep a few addresses for help with future columns.

—W. Robert Smith, Ph.D., Georgia State University

The Monty Hall problem shows, if nothing else, just how unintuitive probability theory can be. It certainly makes me feel much better for goofing up simple arithmetic and probability knowing that Paul Erdős apparently struggled with the Monty Hall problem (see Vazsonyi, 1999).

So what is the right answer, and what did so many people get wrong? The intuitive response is that the probability of Monty Hall opening a door is unrelated to whether there is a car behind the remaining two doors (the one the contestant chose and the final unopened door). Some readers passionately believed that because Monty would always open a door with a goat behind it, this would leave a straight 50% chance the car was behind the remaining two doors, and so there is no reason for the contestant to switch.

A simple application of Bayes' rule shows this to be wrong, however. The answer can be illustrated in different ways, such as using a table or grid of outcomes, a decision tree, pictures or even causal directed acyclic graphs. However, I think it's easiest with just probability theory notation.

Call the event that a car is behind one of the $K=3$ doors $C_{k}$, for $k = \{1, 2, 3\}$, and the event that a contestant chooses one of the doors as $D_{k}$. Similarly, the event that Monty chooses the $k^{\textrm{th}}$ door to reveal a goat will be $G_{k}$. Bayes' rule tells us that the probability that the car is behind one of the two remaining doors after the contestant has chosen and Monty has revealed a goat is:

$$ \begin{split} \begin{align} p(C_{k} | D_{k}, G_{k}) &= \frac{P(D_{k}, G_{k}, C_{k})}{P(D_{k}, G_k)} \\ &= \frac{P(G_{k} | D_{k}, C_{k}) P(D_{k}, C_{k})}{\sum_{i=1}^{K} P(D_{k}, G_{k}, C_{i})} \end{align} \end{split} $$Let's say the contestant chooses door 1, for instance, and then Monty opens door 3 to reveal a goat. Plugging in these terms, we have two conditional probabilities:

$$ \begin{split} \begin{align} \tag{Car behind door 1} p(C_{1} | D_{1}, G_{3}) &= \frac{P(G_{3} | D_{1}, C_{1}) P(D_{1}, C_{1})}{\sum_{i=1}^{K} P(D_{1}, G_{3}, C_{i})}\\\\ \tag{Car behind door 2} p(C_{2} | D_{1}, G_{3}) &= \frac{P(G_{3} | D_{1}, C_{2}) P(D_{1}, C_{2})}{\sum_{i=1}^{K} P(D_{1}, G_{3}, C_{i})}\\\\ \end{align} \end{split} $$The contestant should switch if $p(C_{2} | D_1, G_{3}) > p(C_{1} | D_1, G_{3})$. Assuming there is no bias in which door the contestant chooses and which door the car was placed behind before the show, this reduces to whether the probability of Monty opening door 3 if the car was behind door 2 and the contestant chose door 1 is greater than Monty opening door 3 if the car was behind door 1 and the contestant chose door 1.

$$ \begin{equation} p(G_{3} | D_1, C_{2}) > p(G_{3} | D_1, C_{1}) \end{equation} $$A moment's thought should probably highlight that if the car is behind door 2 and the contestant has already chosen door 1, then Monty has to open door 3 to reveal a goat. Monty has no other option as opening door 2 would have revealed the car. If the car is behind door 1, however, then Monty can open either doors 1 or 2 to reveal a goat. Therefore, $p(G_{3} | D_1, C_1)$ is 50%, but $p(G_3 | D_1, C_2)$ has to be 100%, and the contestant should switch their answer because the conditional probabilities work out more favourable for the other door. Here they are in full.

$$ \begin{split} \begin{align} p(C_{1} | D_{1}, G_{3}) &= \frac{P(G_{3} | D_{1}, C_{1}) P(D_{1}, C_{1})}{\sum_{i=1}^{K} P(D_{1}, G_{3}, C_{i})}\\\\ &= \frac{\frac{1}{2} \frac{1}{9}}{\frac{1}{2} \frac{1}{9} + 0 \frac{1}{9} + 1 \frac{1}{9}}\\ &= 1/3\\\\ p(C_{2} | D_{1}, G_{3}) &= \frac{P(G_{3} | D_{1}, C_{2}) P(D_{1}, C_{2})}{\sum_{i=1}^{K} P(D_{1}, G_{3}, C_{i})}\\ &= \frac{1 \frac{1}{9}}{\frac{1}{2} \frac{1}{9} + 0 \frac{1}{9} + 1 \frac{1}{9}}\\ &= 2/3 \end{align} \end{split} $$Note how the $\frac{1}{9}$ term just cancels in each case, because we are assuming uniform probabilities of a contestant choosing a specific door and the car being placed behind a certain door.

Does this mean the car is actually behind door 2? No. All these probabilities mean is that the evidence is much more consistent with the car being behind door 2 versus door 1.

The Monty Hall discrete mixture model in Stan

It can be instructive to translate some of these probability problems into probabilistic programming languages, such as Stan. We first need to simulate some data, which I'll do using the simple Python function below.

from collections import namedtuple

SEED = 1234

rng = np.random.default_rng(SEED)

MontyHall = namedtuple("MontyHall", ("car", "contestant", "monty", "switch", "correct"))

def simulate_monty_hall() -> MontyHall:

doors = [1, 2, 3]

car = rng.choice(doors)

contestant = rng.choice(doors)

monty = rng.choice(

[

d

for d

in doors

if d != contestant and d != car

]

)

switch = [

d

for d

in doors

if d != contestant and d != monty

][0]

return MontyHall(car, contestant, monty, switch, switch == car)

I then simulated 1,000 different games from this function to use as training data for our model. In my simulation, the average probability of being correct is 67.9%. If we simulated more outcomes, we'd match 66.66666...% more closely.

As I've mentioned in previous posts, Stan can't sample discrete parameters, so we'll have to write the program in a way that marginalises over the different possible doors the car might be behind. In other words, starting from the naive joint density of data (the contestant's and Monty's choice of door, denoted $G$ and $D$ above) and parameters (the probability of the car being behind each door, denoted $C$ above), we need a statement proportional to:

$$ p(G, D, C) = p(G \mid D, C) p(D) p(C) $$We can re-arrange this to marginalise over which door the car is behind by summing out $C$:

$$ p(G, D) = \sum_{k=1}^{K} p(G \mid D, C_{k}) p(D) p(C_{k}) $$We don't really need the $p(D) p(C_{k})$ term, as it just cancels out above when considering uniform prior probabilities, but I'll keep a uniform prior on $p(C_k)$ below to demonstrate how it factors in to the Stan code.

For numerical stability, we'll operate on the log-scale,

and define a Stan variable lp which computes

the log-sum-exponentials

of the above term. I'll also define a Stan data variable

theta that holds the likelihoods,

$p(G \mid D, C)$. Here's the program in full.

data {

int <lower=0> N;

array[N] int<lower=1, upper=3> contestant;

array[N] int<lower=1, upper=3> monty;

array[N] int<lower=1, upper=3> car;

}

transformed data {

int K = 3;

array[K, K] row_vector[K] theta;

// contestant = 1, car = k

theta[1, 1] = [0.0, 0.5, 0.5];

theta[1, 2] = [0.0, 0.0, 1.0];

theta[1, 3] = [0.0, 1.0, 0.0];

// contestant = 2, car = k

theta[2, 1] = [0.0, 0.0, 1.0];

theta[2, 2] = [0.5, 0.0, 0.5];

theta[2, 3] = [1.0, 0.0, 0.0];

// contestant = 3, car = k

theta[3, 1] = [0.0, 1.0, 0.0];

theta[3, 2] = [1.0, 0.0, 0.0];

theta[3, 3] = [0.5, 0.5, 0.0];

}

transformed parameters {

matrix[N, K] lps = rep_matrix(-log(K), N, K);

vector[N] lp;

for(i in 1:N) {

for(k in 1:K) {

lps[i, k] += log(theta[contestant[i], k, monty[i]]);

}

lp[i] = log_sum_exp(lps[i]);

}

}

model {

target += sum(lp);

}

generated quantities {

matrix[N, K] z_probs;

array[N] int<lower=1, upper=3> z;

array[N] int<lower=0, upper=1> correct;

for(i in 1:N) {

z_probs[i] = softmax(lps[i]')';

z[i] = categorical_rng(z_probs[i]');

correct[i] = z[i] == car[i];

}

}

In the generated quantities block,

I compute the posterior distribution of $C$ given

$G$ (called z_probs) by normalising the joint density:

While we know analytically and in expectation

the probability a car

is behind each remaining door conditional on the contestant's choice

and Monty's choice, we can simulate where the car is located

from a categorical distribution using the estimated probabilities,

called z in the code above.

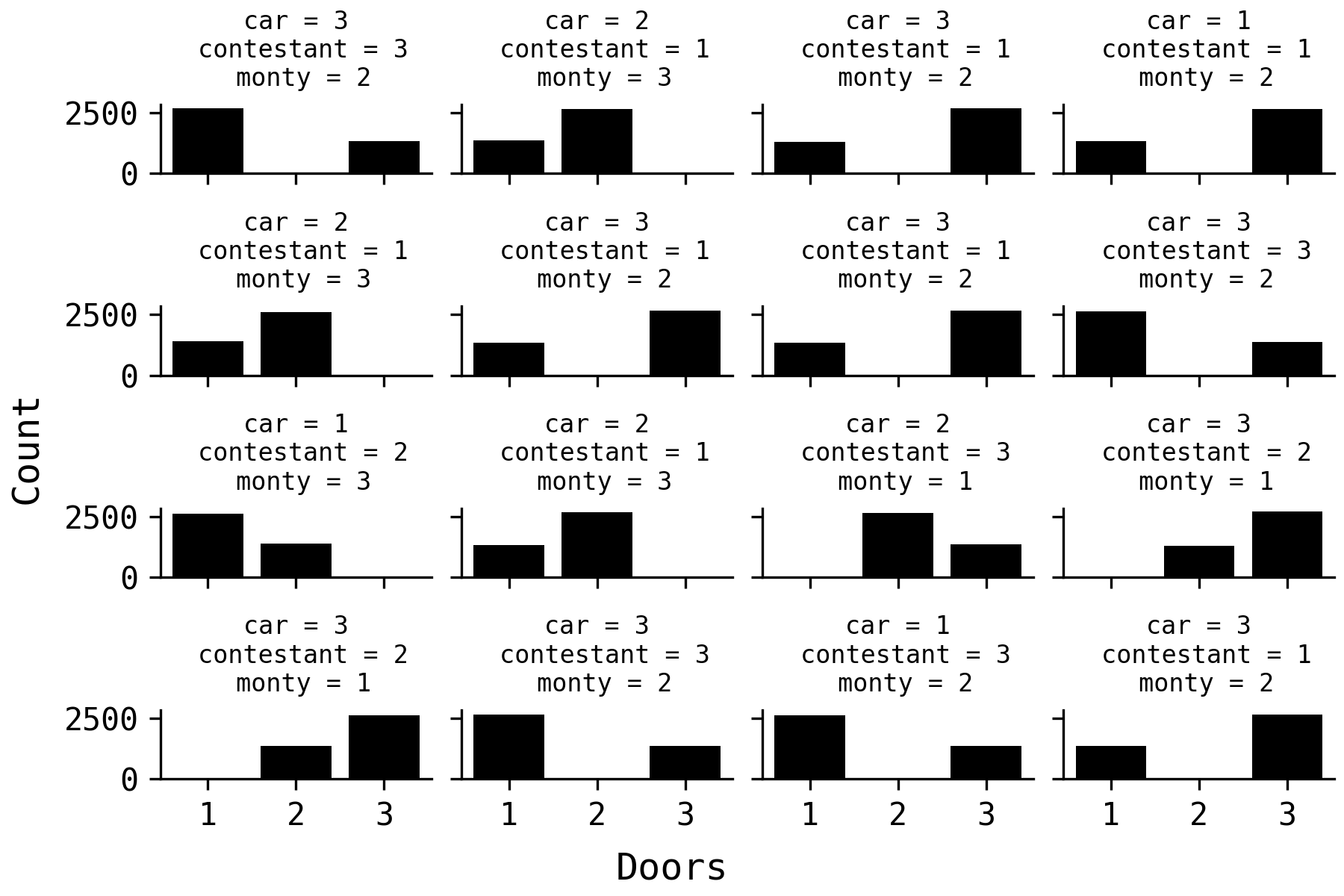

The plot below shows these posterior distributions from the first

16 games in the data.

Computing the expected value of correct choices by taking

the median of each scenario's posterior of z

and the overall mean returns a 67.9% success rate.

This exactly matches the mean success rate from the

data generating scenario.